What is the global sustainable development financing gap?

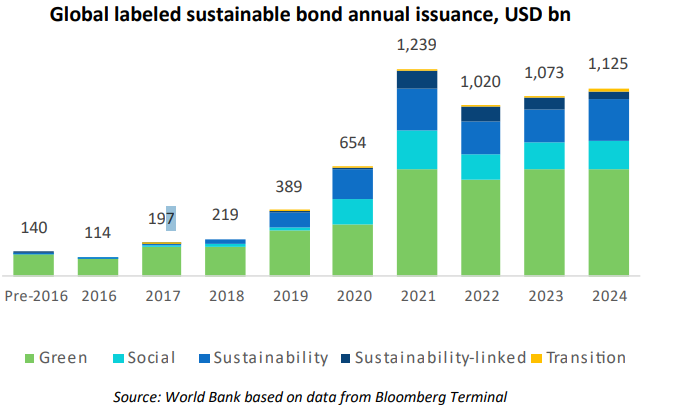

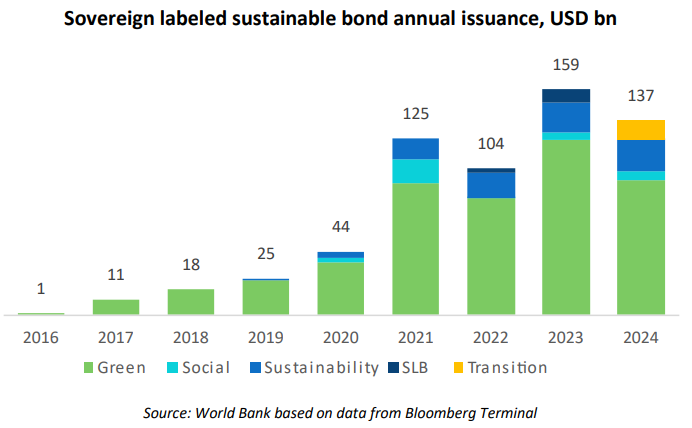

Developing countries face enormous financing shortfalls to meet the SDGs and climate goals. The OECD reports that finance needs for SDGs in emerging economies have surged ~36% since 2015 while available resources grew only 22%, widening the annual SDG financing gap to about $4.0 trillion. Rough estimates suggest even larger climate finance needs – current annual climate investments ($1.5 trillion) are only a fraction of the roughly $7.4 trillion per year needed to achieve a 1.5°C pathway. This “great financing gap” has been exacerbated by debt stress, fiscal constraints and climate shocks (floods, droughts, etc.) in many developing countries. Against this backdrop, thematic sovereign bonds – green, social, sustainability and sustainability-linked bonds – have emerged as one-way governments seek to mobilise new sources of capital for climate and development projects.

Thank You from TRANSFORMATIVEFIN HUB eLearning Centre

Thank you for visiting our website and engaging with our knowledge resources. As a token of appreciation, we're offering you a complimentary copy of the €160 book.

Our elibrary is licensed to give unlimited user access subject to prohibited usage terms including among others resell and free mass distribution. By downloading this book, you accept to abide by the usage terms and conditions.

Let us know which topics matter most to you.

Let us know which topics matter most to you.

— TRANSFORMATIVEFIN HUB eLearning Centre